HOGARTH PRESS

In her diary entry for Monday, 25 January 1915, her thirty-third birthday, Virginia Woolf, describing her birthday ‘treats’, wrote:

I don’t know when I enjoyed a birthday so much – not since I was a child anyhow. Sitting at tea we decided three things: in the first place to take Hogarth [House, Richmond], if we can get it; in the second, to buy a Printing press; in the third to buy a Bull dog, probably called John. I am very much excited at the idea of all three – particularly the press. I was also given a packet of sweets to bring home.

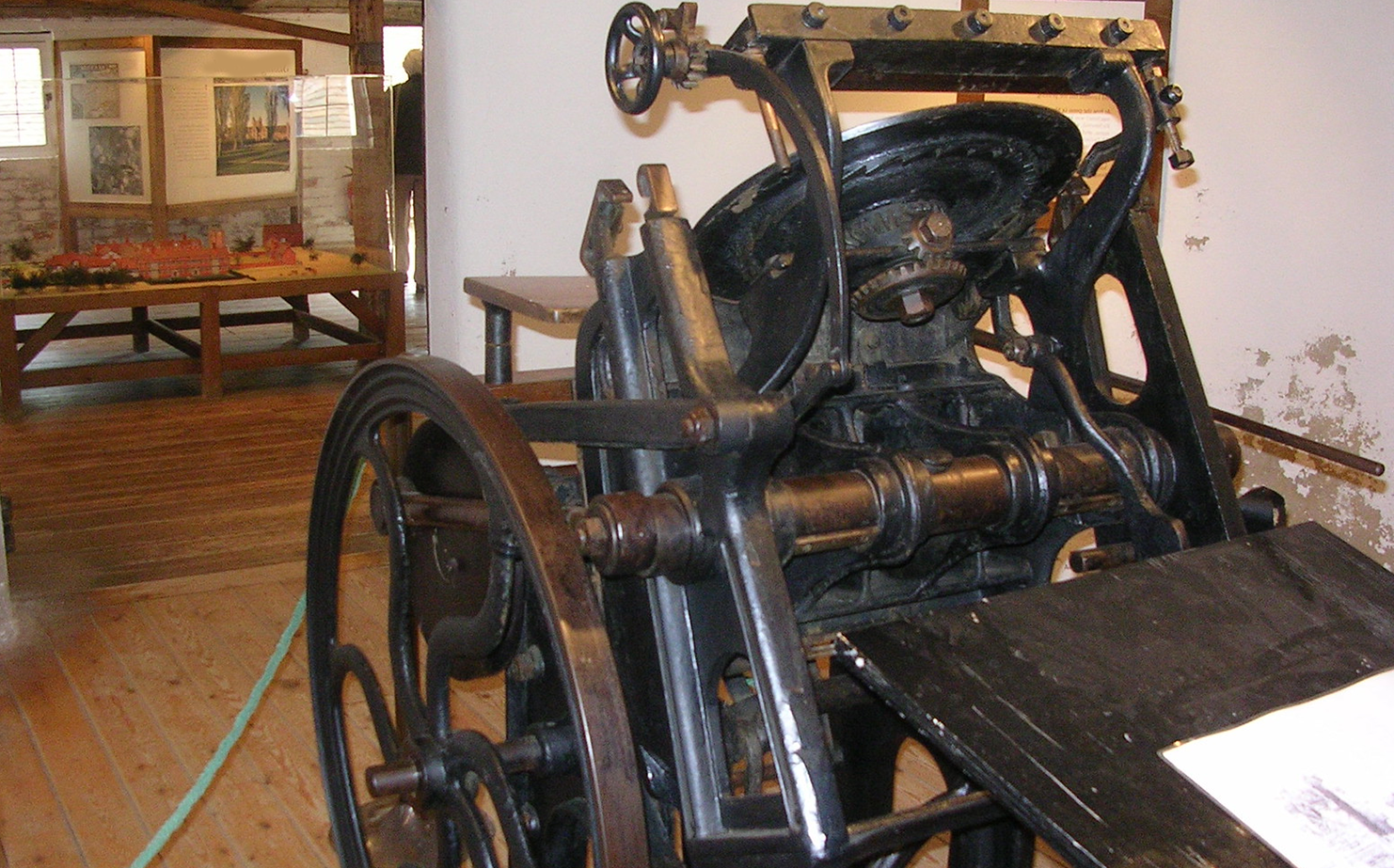

There is no further mention in Woolf’s diaries of John the bulldog, but they soon bought Hogarth House and two years later, they purchased a handpress, thereby merging their home and a small-scale letterpress studio into the Hogarth Press.

After Leonard and Virginia were rejected from the St. Bride’s school of printing because they were not trade union apprentices, they visited Excelsior Printing Supply Co., where they found the machines and materials required for printing. Leonard describes the scene in his autobiography:

Nearly all the implements of printing are materially attractive, and we stared through the window at them rather like two hungry children gazing at buns and cakes in a baker shop window.” They explained their predicament to the shop owner, who encouraged them to pursue printing without taking an apprenticeship course; he sold the Woolfs a printing machine, type, chases, and cases, along with a 16-page pamphlet that would “infallibly” teach them how to print.

It was not until April of 1917 that the press and the typecases were delivered to Hogarth House. She writes to her sister Vanessa Bell:

We unpacked it with enormous excitement, finally with Nelly’s help, carried it into the drawing room, set it on its stand—and discovered that it was smashed in half!

While they waited for their handpress to be repaired, they began distributing the type to be properly stored in the typecases. Virginia wrote that sorting out type was “the work of ages, especially when you mix the h’s with the n’s, as I did yesterday.”

The infinite patience and meticulousness required for letterpress printing, however, did not discourage Virginia; rather, she concluded from these preliminaries, “real printing will devour one’s entire life.” Virginia recounted in her letter that after two hours of typesetting, Leonard “heaved a terrific sigh” and said: “’I wish to God we’d never bought the cursed thing.’ To my relief, though not surprise, he added ‘Because I shall never do anything else.’ You can’t think how exciting, soothing, ennobling and satisfying it is.”

The book arts were not wholly unknown to Virginia; beginning at the age of nineteen, she bound her own books. Thus, at least from her nineteenth year, Virginia had a practical knowledge of bookbinding that complimented her appreciation of books as a reader, novelist, and literary essayist. Woolf’s bookbinding skills—which she continued during the flourishing years of the Hogarth Press—contributed to her favorable inclination, as J.H. Willis argues, towards Leonard’s birthday proposition of purchasing a printing press.

Willis explains:

Collecting books, conversing with sellers of old books, reading for hours in a library, writing at a stand-up desk, or hand binding books…doesn’t lead inexorably to a handpress and a publishing venture at age thirty-three, but these experiences must have predisposed Virginia Woolf to the idea of a press and partly determined what sort of printing and binding she would do with Leonard” (Willis 8)

Leonard recalled that one of the major reasons for beginning the Hogarth Press was to publish small books that would otherwise have little chance of being printed by established publishing companies—small volumes that “the commercial publisher would not look at.”

The majority of Hogarth authors were a part of the Woolf’s Bloomsbury circle—Clive Bell, T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, Roger Fry, Katherine Mansfield, Vita Sackville-West—and they were allowed to escape from the unpleasant pressures of editors and publishers. Yet though the Hogarth Press printed work by Bloomsbury authors, the Press first and foremost allowed both Virginia and Leonard to print their own work, free from editorial censorship.

As Willis notes,

What began as a recreation became a necessity. Virginia Woolf’s genius surely would have survived in some form under any publisher, but it developed as it did in the novels and essays because she was free from editorial pressures, real or imagined, and needed to please only herself” (Willis 44)

The Press additionally gave Woolf the editorial freedom to do as she wished as a woman writer, free from the criticism of a male editor. Indeed, Willis explains that Woolf “could experiment boldly, remaking the form and herself each time she shaped a new fiction, responsible only to herself as writer-editor-publisher…She was, [Woolf] added triumphantly, ‘the only woman in England free to write what I like.’ The press, beyond doubt, had given Virginia a room of her own” (Willis 400).

Though the Hogarth press evolved into a publishing house for Bloomsbury writers, Leonard also initially purchased the press as a form of therapy for Virginia—printing would be a “manual occupation [that] would take her mind completely off her work” (Woolf, Leonard 233). As envisioned by Leonard, the mechanical and physical nature of letterpress printing would liberate her imaginative mind.

However, the printing press became, instead of mental therapy, a form of “aesthetic therapy” for Virginia—it contributed to and changed her work, rather than allowing her to escape writing. Moreover, it bridged the gap between language and reality; language no longer simply conveyed the fictional world, but was composed of real objects to be physically lifted and moved. Indeed, after Virginia became acquainted with type composition, the physical placement and modification of words, required by letterpress printing, is reflected in her writing.

Printing forced her to reevaluate her word choice, punctuation use, and how she built a sentence. Indeed, printing at the Hogarth Press marks the beginning of a new direction in Woolf’s writing, one that playfully experimented with form and composition.

Virginia as a Printer

Artisan placing each letter and the spaces into a compositer that is tightly measured.

Letters and spaces look like this just before the paper is inserted and ink is applied.

Artisan composing movable type for Letterpress Printing.

Through the beginning months of 1917, Virginia learned how to become a type compositor. Because Leonard was plagued with shaking hands, it was impossible for him to properly set type. Thus, while he ran the press machines, Virginia was responsible for the setting and distribution of type.

For each story printed at the Hogarth Press, Virginia needed to set each line, letter-by-letter, word-by-word. The line of type would need to fill the width of the composing stick, packed with differently sized pieces of spacing. Once an entire page was typeset, the block of lead pieces would need to be compressed together so that none of the words would fall out when the page was carried over to the nearby press.

As self-taught beginners, the Woolfs had considerable problems. As Virginia conveyed in her letter to Vanessa, she mixed up the n’s and h’s. When they printed, the ink came out unevenly—thick in some places while too thin on some letters. They didn’t proofread after their initial print, contributing to misspellings and improper punctuation. In addition, both the first notice publicizing the establishment of the Hogarth press and their first publication, Two Stories, had irregular spacing and blotted ink, making their finished product amateurish.

Yet, as biographer Hermione Lee notes, these self-taught amateur printers quickly began to transform themselves into professional publishers.

Printing for Virginia was not a burdensome labor, meant only as a financial supplement to her writing. The Hogarth Press became successful without the structure of a standard publishing business because, paradoxically, they were not interested in the success of the Press. They refused to publish volumes that they did not consider worth printing for their own sake, even though they might make money.

Yet Virginia found the printing process “exciting, soothing, ennobling and satisfying,” and consequently, both Leonard and Virginia developed into professional printers precisely because they found the labor so gratifying.

The Hogarth Press was not only fulfilling on a visceral level; it also profoundly affected how she thought about writing, reading, and the circulation of literature. Indeed, when Virginia began learning about the art of typography and printing, she was simultaneously, as biographer Panthea Reid argues, “discovering how writing could be not invisible but opaque, a signifier in its own right” (Reid 198).

Setting each unit of type with her own hands and arranging the empty spaces between words magnified Woolf’s sense of how a text appears visually on the page. Indeed, Reid explains that in her revision of Melymbrosia, “Virginia had conceptualized language as ‘blocks.’ Now she experienced it literally as blocks of type, an experience that extended her ‘visual literacy’” (Reid 198). Woolf conveys how she imagined words as blocks, objects, or units of individual letters or type in her unpublished essay “How Should One Read a Book?” She writes:

“Try to understand what a writer is doing. Think of a book as a very dangerous and exciting game, which it takes two to play at. Books are not turned out of moulds like bricks. Books are made of tiny little words, which a writer shapes, often with great difficulty, into sentences of different lengths, placing one on top of another, never taking his eye off them, sometimes building them quite quickly, at other times knocking them down in despair, and beginning all over again.”

The process of typesetting is evident within this passage; Woolf stresses that each word should be considered as a single, visual unit, made by a combination of single letters. Moreover, each word is considered like a single block of type; when these blocks are built next to one another or placed “one on top of another,” a sentence is shaped. Hermione Lee comments on this essay, concluding that “The writer is imagined as a kind of mental compositor, and the reader is invited to think of the book not as a fixed object, but as a process—something like the process that goes into type-setting” (Lee 368).

The influence of the printing process on Virginia’s writing style is noticeable in the language she uses when she discusses writing or the composition of a novel. While she was writing The Waves, she wrote in her diary,

Perhaps I can now say something quite straight out; and at length; and need not be always casting a line to make my book the right shape. But how to pull together, how to compose it—press it into one.

She imagines the book as a shape—“made of tiny little words”—which a writer must compose, pull together, and compress into one shape, just as a printer sets type, aligns it with spacing on a composing stick, and presses it into one block.

Heralding the title page of Leonard and Virginia’s Two Stories is the header, “Publication No. 1.” Undaunted by their initial difficulties with their handpress, Leonard and Virginia began setting “Three Jews” in May of 1917, later to be accompanied by and bound with Virginia’s “The Mark on the Wall.”

Printing “Three Jews” was so occupying for the Woolfs that it was only after its complete production that Virginia was able to write “The Mark on the Wall.” Indeed, Virginia was absorbed in the process of typesetting and printing, as she conveyed in a letter to Vanessa: “We have just started printing Leonard’s story; I haven’t produced mine yet, but there’s nothing in writing compared with printing.”

By publishing together in one volume, the Woolfs indicated that the Hogarth Press was a joint enterprise. For Virginia, publishing her story “marked,” as the title suggests, a new direction in her writing, one with a modernist form and experimental language. Indeed, Lee interprets Woolf’s “casual remark” that she had yet to write “The Mark on the Wall” as one of “the utmost significance: the new machine had created the possibility for the new story” (Lee 359).

As the type compositor at Hogarth, Virginia was also confronted with the visual, textual, and linguistic experimentation of other modernist writers, an experience which undoubtedly contributed to her own literary style. Her typesetting skill was tested, not the least of which when the Woolfs agreed to publish Eliot’s epic poem—Eliot even inscribed Leonard’s copy of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by calling him his “next” and “second publisher” (Woolf, Leonard 242).

They began production in early 1923; Virginia typeset the poem herself and Leonard printed the text. By July, Virginia wrote:

I have just finished setting up the whole of Mr. Eliots poem with my own hands: You see how my hand trembles

The Waste Land was one of the most typographically challenging works to be published by Hogarth, or for that matter, to be typeset by Virginia. Eliot was skilled in adroit spacing with lines indented to the center of the page or beginning near the border edge, making it difficult for a typesetter to perceive his intended space.

This edition of The Waste Land was particularly important to its publishers, Leonard and Virginia Woolf. Leonard Woolf wrote: “As an amateur printer and also the publisher of what I was printing, I found it impossible not to attend to the sense and usually after setting a line and then seeing it appear again as I took it off the machine, I got terribly irritated by it. But I never tired and still do not tire of those lines which were a new note in poetry… (and sounded with even greater depth and volume in the next work of his which we published), the poem which had the greatest influence upon English poetry, indeed upon English literature, than any other in the 20th century: The Waste Land” (quoted in Rhein, p.22). Rhein notes that despite its earlier appearances, the Hogarth Press edition of The Waste Land was a special event: “Publishing The Waste Land increased the Woolfs’ prestige and that of the Press enormously. It also encouraged Eliot, who was still working at Lloyd’s bank, to keep writing” (Rhein, p.24). Gallup A6c.

When the Hogarth Press edition of The Waste Land was finally published in September of 1923, with navy blue marbled boards most likely prepared by Vanessa, and nine months after the appearance of the American edition by Boni and Liveright, Eliot was vastly pleased by the appearance of the Hogarth volume. In a letter to Virginia, Eliot complimented the Woolf’s setting of his poem, recognizing the effort taken to print his difficult work, and deeming it superior to the Boni and Liveright edition (Willis 72).

When the Woolfs moved from Hogarth House, Virginia wrote in her diary:

Nowhere else could we have started the Hogarth Press, whose very awkward beginning had rise in this very room, on this very green carpet. Here that strange offspring grew and throve; it ousted us from the dining room, which is now a dusty coffin; and crept all over the house.”

Woolf’s comparison of the dining room to both a womb and a coffin, with the press as its growing child, conveys her emotional attachment to the press. After Leonard left editing the Athenaeum, Virginia wrote:

We are now supporting ourselves entirely by the Hogarth Press, which when I remember how we bought five pounds of type and knelt on the drawing room floor ten years ago setting up little stories and running out of quads…makes my heart burst with pride.

Both of these passages convey the importance of the press to Virginia. The press progressed from the initial frustrations and delights of letterpress printing, to the more time-consuming activities of a full-time publishing company, where the Woolfs read and edited manuscripts and interacted with managers and assistants.

J.H. Willis argues that the press:

Objectified Woolf’s world, allowing her to keep…in touch with young writers, new movements, women’s affairs, politics. It strengthened the bond with her sister Vanessa by bringing Virginia’s verbal art together with Vanessa’s visual arts in the texts, illustrations, and dust jackets of the sister’s joint press publications (Willis 400).

The Hogarth Press published over 525 books within a period of thirty years; considering Virginia’s intense involvement in the burgeoning years of the press, it is important to consider what was needed for each of her books to be articulated, both physically, with her letterpress typesetting, and mentally, with how she composed language.

Source: https://campuspress.yale.edu/modernismlab/hogarth-press